Toldot — The “Over Praise” Theory of Esav

How Esav’s birth and early years made him into who he was

Why did the two twins, Esav and Yaakov turn out so differently? Specifically, what went wrong with Esav? I have a theory — it is my “Over-Praise-Theory” of Esav.

From the moment he was born, Esav was different. Extraordinary.

וימלאו ימיה ללדת והנה תומם בבטנה ויצא הראשון אדמוני כלו כאדרת שער ויקראו שמו עשו

When the time came for her to give birth, there were twins in her womb. The first one came out reddish, as hairy as a fur coat. They named him Esav [my emphasis] (Genesis 25:24–5)

“Admoni” means that he was born red-haired, but Chizkuni translates it as “manly.” Esav emerged from the womb a completed man: אדם נגמר כולו היה עשו. Besides being born mature and hairy, the verse adds that “they” called his name “Esav” (which means “made” or “completed”.) Who were the “they” who called him Esav? It was not both of his parents because in the next verse, Yitzchak alone who names Yaakov. (1)(The next verse reads, “He named him Yaakov.”) It is unlikely that Rivka took part in naming Esav but suddenly lost interest moments later when it was time to name his twin brother.

So who were the “they” who named Esav? I say it was the locals — when Esav was born, no-one had even seen a baby like this: not only was he hairy but he was mature. So here was a phenomenon. Something extraordinary. Something no-one had ever seen before. He was the talk of the community, and it was they who called him Esav. True, Yitzchak also called him Esav; but even before he was named, Esav was already being called that.

In contrast, Yaakov was a regular baby, and he was only named by his father.

Imagine the consequences of twin boys, one a regular baby and one highly unusual. The unusual boy is known by everyone, recognized by everyone, identified by everyone. (“Do you know what he looked like when he was born? Let me describe it to you. No-one had ever seen anything like it.”)

Esav grew up a precocious young kid, who was noticed by everybody. What is the natural response of being someone used to being noticed by everybody? To stay in the public eye. (If you need to be noticed by people, you need to be where the people are.) Esav literally stays outside, indeed, Esav becomes an outdoorsman:

The boys grew up. Esau became a skilled trapper, a man of the field (Gen 25:27)

It would not be a surprise to find Yaakov’s motivation is to be the non-Esav. (On bumping into the twins: “You must be Esav! And you must be… Esav’s brother.”) And that is what happens:

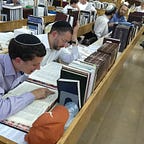

Jacob was a scholarly man who remained with the tents. (Gen 25:27)

What then are the consequences for an Esav, a child noticed by others from birth, and being the oldest — and long-awaited — grandson in a prominent family? He keeps being noticed, and praised. And this, I suggest, was the root of his downfall. Carol Dweck, the psychologist most famous for her work on the “growth mindset” has also written about the risk of praising children for their intelligence:

Dweck discovered that those who think that innate intelligence is the key to success begin to discount the importance of effort. I am smart, the kids’ reasoning goes; I don’t need to put out effort. Expending effort becomes stigmatized — it’s public proof that you can’t cut it on your natural gifts.

Living up to the birthright would take effort! But Esav, raised on a steady diet of public attention and praise, was uninterested in effort. So he despised the birthright. (Gen 25:34).

(As an aside, my “Over Praise” theory of Esav also explains the conduct of Yitzchak and Rivkah which was criticized by Rav Hirsch. Rav Hirsch (in his comments on Gen 25:27), based on Bereshit Rabba 63:10, criticizes Yitzchak and Rivka for raising Yaakov and Esav identically. Instead, they should have educated them in a manner more fitted to their individual personalities. After all, Proverbs 22:6 does tell us to “Train a child in the way he ought to go; He will not swerve from it even in old age.” חנוך לנער על פי דרכו גם כי יזקין לא יסור ממנה

The Midrash that he cites, interestingly, does not criticize Yitzchak and Rivka. The Midrash compares Yaakov and Esav to “a myrtle and a stinging plant growing side-by-side” — the observation being that they were raised the same way but they were destined to end up opposites.

The “Over Praise” theory of Esav explains why Yitzchak and Rivka chose to raise Esav and Yaakov identically. It was because they saw the excess attention that Esav had always received (and Yaakov’s subsequent withdrawal into the tent of scholarship) that Yitzchak and Rivka felt they had to show their sons that in their eyes, they were of equal value. The two of them would therefore receive the same education.

They made the choice deliberately, not because they did not recognize the difference between their two sons. Their actions made the following statement: “We refuse to be influenced by the attention our neighbours have always paid to Esav’s appearance and precocity. To us, the two of you are of equal worth.”

Notes

(1) The verse does not explicitly say Yitzchak named Yaakov. As is common in Biblical Hebrew, the verse presents a verb without a subject: ויקרא שמו יעקב ויצחק בן ששים שנה “He named him Yaakov. And Isaac was 60 years old…” It does not explicitly say who did the naming of Yaakov. The plain reading is that it was his father. But according to Rashi, it was Hashem who named Yaakov.

(2) “How Not to Talk to Your Kids” by Po Bronson, New York Magazine, February 9, 2007 https://nymag.com/news/features/27840/ . Carol Dweck: “When we praise children for their intelligence, we are telling them that this is the name of the game: Look smart; don’t risk making mistakes . On the other hand,when we praise children for the effort and hard work that leads to achievement, they want to keep engaging in that process.They are not diverted from the task of learning by a concern with how smart they might — or might not — look.” From “Caution — Praise can be dangerous” in American Educator, Spring 1999. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/PraiseSpring99.pdf